Image courtesy of sangres.com

A scenic stretch of State Route 89A — the Jerome-Clarkdale-Cottonwood Historic Road — overlooks the Verde River Valley, exposing spectacular views of the Mogollon Rim and Colorado Plateau. As travelers approach from Prescott on State 89A, a steep drop followed by a final hill pitches right onto Main Street in the heart of Jerome and the start of the historic road designated in May 1992.

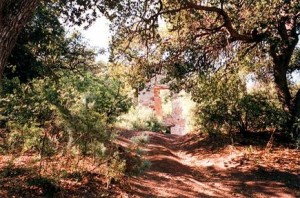

The once-roaring mining community became a ghost town and then transformed into today’s thriving art community, all while clinging precariously to the side of Cleopatra Hill. Buildings balance cautiously, clutching the steep grade. Retaining walls and flat pads hold some structures in place, while others hang on at seemingly impossible angles. Headlines in the February 5, 1903, issue of the New York Sun read, “This Jerome is a Bad One — The Arizona Copper Camp Now the Wickedest Town.”

Jerome started as a mining camp, nothing more than a settlement of tents. But the surrounding hills were full of copper, and soon a lawyer named Eugene Jerome invested $200,000 in a mining operation to extract it. His claim would eventually make Jerome one of the largest towns in Arizona. He also hired a surveyor to lay out the twisted town of Jerome, a namesake he insisted upon although he never visited there.

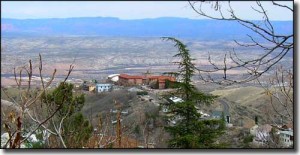

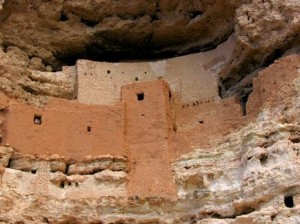

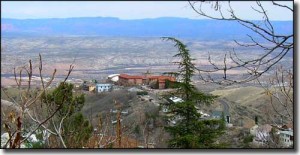

But Eugene Jerome wasn’t the first to discover the abundance of minerals in the Black Hills. Indian tribes in the region were well aware of the riches beneath the mountains long before the Europeans and Spanish entered the area. Somewhere around the year AD 1125, the Sinagua Indians appeared in the Verde Valley, a lush forested land with a dependable water source in the rushing green-blue of the Verde River. They lived a prosperous life, trading with tribes more than 100 miles away and farming the rich valley. Around the year AD 1400, the Sinagua people inexplicably began to migrate from the region. By the year AD 1450, they had disappeared, but left behind a dwelling now called Tuzigoot, an Apache word for “crooked water.”

The 110-room, two-story ruin perches atop a hill between the towns of Cottonwood and Clarkdale. The Sinagua Indians knew of the minerals in the hills and used them to trade for other necessities and pleasures of life, like copper bells and pottery more elaborate than their own brown clay and volcanic ash pieces. Occasionally they used azurite, a mined copper carbonate with a deep-blue hue, to paint their pottery. The museum at Tuzigoot National Monument displays some of their jewelry.

After the Sinagua people disappeared from the area, Spanish explorers stumbled across the land following tales of gold-laden cities and mines with rich veins of colored ore. Many years later, the first American prospectors came, soon to uncover and exploit the multitude of riches buried deep in the Black Hills. On a search for gold in 1583, Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo and his companions traveled through the desert surrounding Jerome and the Black Hills. Greeted by the Indians of the region who gladly showed the explorers their own mining efforts in the hills, the Spaniards had their hearts set on gold. When they realized the Indians were mining mainly copper, they decided to move on, but claimed the land in the name of Spain. They were unaware of the great fortunes that lay waiting just below their feet — copper mostly, but also silver, gold and zinc.

In 1598, Marcos Farfan, also a Spanish explorer, crossed the area looking for gold. He, too, claimed the mines for the Spanish crown, but the rough mountains deterred him. The small amount of gold mixed in with the copper, he believed, was not worth the great effort to remove it. After these two explorations, it would be almost 300 years of only scattered visits from the Spaniards and Anglos before the mad rush for riches brought the miners that would change the area forever.

American settlers arrived in the Verde Valley in 1865, wandering in from the Prescott Valley area. Small-scale mines attempted to extract the precious metals from the mountains, but the difficult desert terrain and rocky mountainsides made excavation uneconomical. Finally a group of prospectors, including future Territorial Governor Frederick A.Tritle, acquired an interest in some of the claims. The work was hard and hot, and the men made $80,000 before transporting the ore became too expensive to continue.

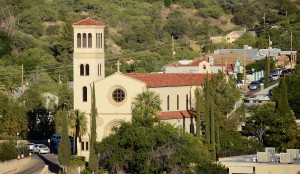

Enter Eugene Jerome, a New York moneyman looking for an easy buck. His investment gave the first breath of life to the United Verde Copper Co. and the twisted face-lift of rickety buildings and zigzag roads that adorn Cleopatra Hill. Jerome owned it all — the mining operation and the town — but in 1888 he sold it to William Andrews Clark, a US senator from Montana and a copper mogul who knew exactly what it would take to profit from the mines in Jerome, and he had the capital to make it happen. Fires deep in the mines forced the company to begin open-pit mining, and the old smelter that sat on top of the mines had to be removed. Clark started construction on a new smelter in 1910 just down the road from Jerome, and then in 1914 built a town around it named Clarkdale. Clarkdale’s historic district is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places as one of the first successfully planned company towns. Clark also financed a narrow-gauge railroad line to connect to the Santa Fe railroad, forging the final link to the outside world.

When the mine pumped profits into Clark’s pockets and attracted miners looking for work, the entrepreneurs came also. Bars, brothels, hotels, saloons and boarding houses all popped up, and Jerome became the bad, brawling, billion-dollar mining town that endured many mining deaths, smallpox and scarlet fever epidemics, and a series of devastating fires that ravaged the mountainside buildings between 1897 and 1899. But Jerome survived. The town incorporated in early 1899 and established the Jerome Volunteer Fire Department as well as a building code advising construction with brick and stone to help prevent further fires.

By the 1920s, Jerome had a population of about 15,000 and was the largest copper-producing area in Arizona, but production slowed with the Great Depression of the 1930s. The mine came into the hands of the Phelps Dodge Corp., which still owns it. During the 1930s Phelps Dodge used dynamite blasts in the open pits to go deeper for ore, and in the process made Jerome a “moving” community — literally. Shifting earth caused by the great blasts made parts of the town crack and slide. One large blast caused an entire downtown block to slide one level down the mountain, and resulted — to some amusement — in the relocation of the town jail, which slid a full block from its original site.

The increased demand for copper during World War II revived the mine for a while, but in 1953 the mine closed after more than 70 years of production. Approximately $800 million in copper had been taken from the veins of the mighty mountains. With the closing came the inevitable death of the town as a mining center as miners dispersed across the Southwest looking for work. The 50 to 100 diehards who remained began promoting Jerome as a ghost town, and in 1967 the US government declared Jerome a National Historic Landmark.

Despite the ravaging fires that destroyed much of Jerome in the late 1890s, many of the original buildings still stand and many more have been restored. The spicy flavor of a wild mining environment still permeates the town. Today, known primarily as a tourist attraction and art community, Jerome greets approximately a quarter of a million visitors a year. Leaving Jerome, the first 6 miles of the drive to Cottonwood drop steeply and offer awe-inspiring views of the Mogollon Rim and the Verde Valley. Surrounded by mesas and buttes to the north, and jagged mountains in every other direction, Cottonwood got its name from the cottonwood trees that grow along the Verde River, which runs right through the town.

Cottonwood began as a camping place for travelers headed for Oak Creek and Camp Verde, and was a main crossing place on the Verde River. The first Anglos to settle here were soon followed by soldiers from nearby Fort Whipple, who were sent to protect ranchers in the Verde Valley. The fertile land soon attracted other ranchers and farmers, and a small farming community sprung up.

Today, Cottonwood has a population of about 5,900. A quaint area known locally as Old Town is officially Cottonwood Commercial Historic District. Walking tours are offered as are self-guided tours of the Verde River riparian area. At the end of the Jerome-Clarkdale-Cottonwood Historic Road southeast of Cottonwood, the next leg of the journey starts toward Sedona — the Dry Creek Scenic Road.

Article courtesy of Arizona Scenic Roads.